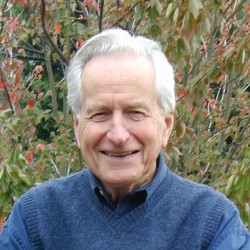

John Goodlad

John I. Goodlad is Professor Emeritus in the College of Education and co-founder of the Center for Educational Renewal at the University of Washington as well as President of the Institute for Educational Inquiry in Seattle. While he has previously held faculty positions at Emory University, the University of Chicago, and the University of California at Los Angeles, Goodlad first taught in a one-room, eight-grade school house in British Columbia, Canada. His experiences as a classroom teacher encouraged his later educational research examining grading procedures, curriculum inquiry, the functions of schooling, and teacher education. Recognized for his distinguished contributions to educational renewal, Goodlad drew national attention and spurred research efforts on school improvement through his award-winning book, A Place Called School (1984). Honored for his lifelong commitment to universal education as a mainstay of democracy, Goodlad has received numerous awards and honorary degrees including the Harold W. McGraw, Jr. Prize in Education (1999), the first Brock International Prize in Education (2002), and the John Dewey Society Outstanding Achievement Award (2009). Goodlad has authored or edited more than three dozen books, 200 articles in scholarly publications, and 80 book chapters and encyclopedia entries. His more recent publications include: In Praise of Education (1997), Education for Everyone: Agenda for Education in a Democracy (2004), and Romances with Schools: A Life of Education (2009).

To learn more about John Goodlad from his family and friends, visit his Reflections. To view photographs from John Goodlad’s personal collection, visit his Photo Gallery.

Curriculum Vitae Suggested readingsVisit the video below to watch a short overview of the interview with John Goodlad. Otherwise, see all six of the full interviews with John Goodlad below.

Video Interviews with John Goodlad:

Raised with his brothers in Vancouver, British Columbia, Dr. John Goodlad spent his childhood exploring the nearby mountains and playing sports with other young boys in the neighborhood. Although Goodlad immensely enjoyed reading, he resisted going to school, even attempting to run home on the first day! Despite Goodlad’s advanced reading ability, his parents were initially advised that he should repeat first grade. However, at his father’s insistence, Goodlad proceeded uninterrupted to the next level and eventually skipped ahead an entire year. Watch this clip to hear stories about Dr. Goodlad’s favorite teacher and learn how the Great Depression shaped his own career path.

In his early years as a teacher, Dr. John Goodlad taught in a rural one-room, eight-grade school house with few books or supplies and a modest yearly salary. Frustrated with the prescribed curriculum and rigid grading procedures, Goodlad used innovative instructional strategies to engage his students, many of whom had already been retained in the same grade several times. Goodlad expresses his disappointment in schools today that focus almost exclusively on the direct impact of teachers on student learning, arguing that the functions of schooling also include interactions with families and the zeitgeist or spirit of a school. In this clip, learn more from Dr. Goodlad about the need for practice-driven research in the field of education.

Convinced that grade retention is detrimental to students both academically and socially, Dr. John Goodlad has served as an advocate for nongraded elementary schools throughout his career. As a graduate student at the University of Chicago, he examined the effects of grade promotion and retention on students who had produced work of similar quality and challenged critics who argue that nongraded schools based on students’ interests are impractical at best. Citing more than 100 years of research, Dr. Goodlad insists that student classification practices must be reconsidered. Watch this clip to share Dr. Goodlad’s passion for student learning and learn more about his role as a leader in education improvement.

Likening schooling to an industrial-age assembly line, Dr. John Goodlad describes the frustration and lack of motivation experienced by workers who never saw the finished product. He identifies a similar problem in schooling whereby teachers and parents rarely discuss educational outcomes. Founded by Goodlad to spur dialogue about issues in education, the National Network for Educational Renewal creates a space for interaction between arts and science experts, school teachers and administrators, and university researchers. In this clip, learn more about Dr. Goodlad’s innovative ideas for improving teacher education and communication among those concerned with educational renewal.

Recognized for his groundbreaking study of more than 1,000 schools across the United States in A Place Called School (1984), Dr. John Goodlad recalls an article about his book featured on the front page of the New York Times. Despite his message of optimism and improvement, Goodlad explains that most reporters contacted him after publication, requesting more “dirt” on schools. Carefully noting the need for educational renewal rather than reform, Goodlad describes collaboration among teachers and parents as the most meaningful way to improve American schools. Praising these stakeholders as vital to the renewal process, Goodlad insists that “agency must be closest to the child.” Watch this clip to hear more from Dr. Goodlad about “inexcusable malpractice” in schooling and the teachers who inspire him most.

Deeply appreciated by his students long after they have left the classroom, Dr. John Goodlad remains at the forefront of educational renewal. Readily challenging those who follow traditional fingerposts in education as guides for school improvement, Goodlad explains that “ideas are easy to come by but hard to do.” Goodlad, inspired by his late wife to demand “education for everyone,” continues his commitment to quality schooling through collaboration with colleagues in the field. In this clip, enjoy stories about Dr. Goodlad from the family and friends who know him best.

Amrein-Beardsley, A. (2012, April 20). Inside the Academy video interviews with Dr. John Goodlad [Video files]. Retrieved from /inside-the-academy/john-goodlad

Dr. Dick Clark

Having worked closely with Dr. John Goodlad on various projects over the past three decades, Dr. Dick Clark recalls his positions at the Center for Educational Renewal at the University of Washington and the Institute for Educational Inquiry for which he was the “chief worrier” for several grant projects and studies conducted by his long-time friend and colleague. Dick also notes John’s sense of humor, describing his comical reaction to the concerns of a colleague regarding the development of school-university partnerships designed to improve the quality of schools and teacher preparation. When asked about his willingness to consider “different views about such partnerships, [John] stood up, took off his jacket, and vigorously rolled up his sleeves” asserting that he had nothing to hide. Friends and colleagues still recall this incident as symbolic of his approach to research. Expressing their “mutual frustration with what [they] see as inexcusable malpractice by policymakers and educators who are shaping today’s schooling practice,” Dick praises his friend for “his persistence in pursuing fundamental ideas and goals,” namely his advocacy for ungraded schools and the study of teacher education. Also well-known for his comprehensive study described in A Place Called School (1984), John has remained “committed to the principle enunciated by John Dewey that education is not preparation for life; education is life itself.” Dick also cites John’s promotion of “active engagement with practitioners in the field by researchers.” Dick describes the essence and nature of his friend John, explaining that his “determined commitment to ideas that are not deterred by concerns from others who are quicker to see problems than they are to see potential” has shaped his work as a researcher and scholar.

Learn more about John Goodlad from his friend Dick Clark.

Dr. Eugene Edgar

Dr. Eugene Edgar describes his friend and colleague Dr. John Goodlad as “a true community organizer,” explaining that he “organizes spaces wherever he finds himself [and] would make Saul Alinsky proud.” Serving as the chair of the board of directors of the Institute for Educational Inquiry, an organization founded by John to advance the Agenda for Education in a Democracy through professional development for educators, Gene notes John’s successful establishment of the agenda “as a core idea in the educational worldview of the majority of educators in the United States.” His commitment to “clear and defensible goals for schooling in a democracy” is particularly important as “the purpose of schooling [in America] is continually being challenged.” Recalling his friend’s capacity as a leader in multiple contexts, Gene describes John’s recuperation after a recent knee surgery. Spending several weeks in a medical care facility, John quickly “noted a number of organizational procedures that could be improved and joined a patient advocacy group that included other former deans.” The group developed a series of recommendations for the organization in no time at all! Admiring John for his tireless dedication to the improvement of schools, Gene characterizes his long-time friend as “chock full of wisdom and unending gumption.”

Dr. Gary Fenstermacher

Dr. Gary Fenstermacher first encountered Dr. John Goodlad, then Dean of the Graduate School of Education at the University of California at Los Angeles, from across the desk at a job interview for a faculty position. Although he hadn’t the “foggiest idea who John Goodlad was,” Gary later accepted the position, noting that “the finest and more lasting aspect of that position was-and still is-[his long-time friend and colleague].” Explaining that he was “much more than a dean,” Gary characterizes John as “an extraordinary mentor, superb colleague, very good friend, and yes, my cultural hero.” For his encouragement of Gary’s interests in teaching and teacher education, John “served as a model for educational policy and reform that is evidentially grounded, morally robust, and democratically compelling.” Gary adds that one “cannot read the Goodlad corpus and miss his immense regard for human potential-of the student, the teacher, the parent, the school administrator.” Comparing John to Plato, John Locke, and John Dewey for his ability to situate his work in ethical and political theory, Gary praises John for his studies of teachers, teaching, and schools. In addition, Gary credits John for profoundly influencing what he seeks to be as a philosopher and person. Recalling his friend’s kindness during a difficult time, Gary describes the beautiful stuffed toy (a dolphin) given to his son by John and his wife. Gary still tears up when he thinks of it-the dolphin was his son’s favorite toy until it disintegrated years later. When asked to capture the essence and nature of his friend, Gary characterizes John as “magnanimous, considerate, generous, serious, discerning, committed, brilliant, gracious.” Learn more about John Goodlad from his friend Gary Fenstermacher.

Dr. Ann Foster

Describing her first meeting with Dr. John Goodlad, Dr. Ann Foster recalls their discussion about his then recent publication, A Place Called School (1984), and adds that they “visited like long-time friends.” While initially connected to John’s work through the Colorado Partnership for Educational Renewal, Ann later worked directly alongside him as the Executive Director of the National Network for Educational Renewal. Explaining that John has “nurtured an ecology of renewal within the education profession,” Ann notes that his “accomplishments are multidimensional and interactive.” In a “complex [education] system where each decision and action affects the overall health of the ecology,” his “clear focus ([on] the Agenda for Education in a Democracy) creates a coherent purpose,” nurtured through “his writing, in his research, how he structures professional development, how he interacts with colleagues, and through the new initiatives he develops.” Ann explains that John “never loses sight of the whole ecology and attends to the big questions and the daily needs of learners.” As he is also an avid fan of jazz music, Ann remembers having “many good conversations on the state of education and the world while sitting around the warm fire.” John would pause every once in awhile to “listen or hum along to a favorite tune.” Praising her friend as “intellectually curious,” Ann explains that John is always “seeking new information about everything and everyone around him.” Ann captures John’s essence and nature through his love of learning, noting that “he listens thoughtfully, engages eagerly with varying perspectives, converses with whatever author he is reading, and genuinely appreciates others’ contributions to conversations large and small.”

Robert Goodlad

Robert Goodlad shares his early memories of Dr. John Goodlad as “Uncle John,” describing him as a “mythical uncle” who was respected and admired by others in the family. Recalling their image and understanding of their uncle as children, Robert and his sister Jane remember their grandmother’s great fondness for her son. Carrying that mystical belief into adulthood, Robert describes his interactions with teachers who asked about the work of his well-known uncle. In recent years, Robert and his sister have been delighted with the opportunity to “build a relationship with [their uncle] in a personal way,” often visiting his home in Seattle and island retreat. Admiring his “strong belief in public education based on a foundation of democratic principles,” Robert praises John for his ability to “share his ideas about education in a way that influences teachers far removed from his university setting.” Robert notes that “in simple language, [John] explains the serious faults [of] delivering education in the school system today yet more importantly explains a way forward in lay terms.” John’s experiences “teaching grade school kids in a non-standardized, non-graded way [influenced] his long-term ideas about education.” Characterizing his uncle as humble, Robert explains that John has had “an outstanding career as a prominent educator and articulate, prolific communicator.” In the eyes of his nephew, John “expresses [his] impassioned beliefs with clarity and urgency [because] in his soul [he] knows the importance of good education and how to go about it.”

Dr. David Imig

Characterizing Dr. John Goodlad as “dapper, engaging, indefatigable, and loquacious,” Dr. David Imig readily admits that he was “in awe” long before having his first genuine opportunity to spend time with the distinguished scholar. David had been commissioned to travel to Seattle and personally invite John to consider a position as the president of the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education. This formal introduction at an old hotel on the edge of the University of Washington campus marked “the beginning of a deep and meaningful relationship” between David and his “mentor, friend, and professional colleague.” Recalling later meetings of an advisory group formed by John, David describes how he and another colleague, Gary Fenstermacher, would sit at the end of the table and offer “commentary on what was transpiring.” David recalls that “John tolerated our misbehavior but then decided he would reseat us.” Foiling John’s plans to separate them, David and Gary spent their coffee break rearranging the cards (“name tents”) that John had put in place. John’s pointed references to his early experiences as a teacher at a reform school for boys in British Columbia and his description of David and Gary as “errant children” remains one of David’s fondest memories. Widely recognized for his celebrated work Teachers for Our Nation’s Schools (1990), John attended a two-day celebration of the book’s release at the Smithsonian Institution’s Castle on the Mall in Washington, D.C. David explains that “few of the participants understood that every word had been painstakingly written by John by hand with multiple drafts and much editing to produce the single most important book on the role of schooling in a political democracy.” According to David, John is always “reticent to accept praise” even when recounting his role in an earlier study undertaken by James Conant in the early 1960s. Although the results of the study later shaped his own investigation of teacher education, John and his colleague Michael Usdan compared themselves to “little more than bag carriers…for Conant and his intrepid band of 15 prominent educators.” John insisted that he “ensured that the Harvard President’s luggage was transported appropriately” to some 77 institutions in 22 states! Also inspired by John’s own account of his experiences as a teacher in a one-room school house in Romances with Schools (2004), David summarizes the fundamental question posed in the book: “What would it be like if every student could have a true romance with their school?” David further explains that the “essence of John Goodlad emerges in those pages-he is ambitious and driven, self-disciplined, and demanding of himself and others.” “His is a dominant voice for goodness in the way that we approach the challenge of schooling young people.” For David and no doubt countless others, “he is a true giant of 20th century American education with a message for all for the future.”

Dr. Corinne Mantle-Bromley

While serving as an assistant professor at Colorado State University, Dr. Corinne Mantle-Bromley first encountered Dr. John Goodlad through a leadership program developed by the Institute for Educational Inquiry for the National Network for Educational Renewal (NNER). This group convened four times per year in Seattle to “discuss purposes of education: issues of equity, moral qualities and imperatives.” Cori describes the reading requirements as “significant” but also “a joy to read and discuss, oftentimes with the books’ authors, and especially with John.” Later invited to accept a position as Executive Vice President of the Institute for Educational Inquiry, Cori welcomed the opportunity to support the NNER, a consortium of school-university partnerships that promoted the Agenda for Education in a Democracy. Having worked collaboratively with John for more than five years before returning to higher education, Cori continues to admire him for his “steadfast support of schooling and its connections to our democracy…[and for his] care for the quality of schooling young people receive that permeates his work.” She adds that “his insistence on collaboration between schools and universities has been long present and is just now getting the attention it should have had for years.” Explaining that “unfortunately, many do not know that the bringing together of the two cultures is in many ways because of the steady work he and those working with him did for years,” Cori cites the continuation of the NNER as one of her friend and colleague’s most significant accomplishments. Capturing John’s essence and nature as a researcher and scholar, Cori characterizes him as “intellectually curious, interdisciplinary in his reading, understanding, and confident.”

Dr. Nicholas Michelli

Dr. Nicholas Michelli describes Dr. John Goodlad as “his friend and the most important mentor in his professional life.” Having used films of John and the IDEA project on school change in his college courses, along with his books,” Nick recalls his nervousness when meeting John years later at an American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education board meeting. Carefully positioning himself to be near the President-Elect, Nick adds that “he was, of course, one of the most open and welcoming individuals that [he] has ever met.” Nick describes his own subsequent work with the National Network for Educational Renewal as “the most important work” he has done. Having long since admired his friend, Nick later decided to use the name “Goodlad” as the code word for his home security system to be given over the phone in the case of a false alarm. Recalling a comical incident whereby the alarm sounded as a result of a small cooking fire, Nick responded to the phone call, saying “Goodlad, Goodlad, Goodlad.” To his surprise, the voice on the other end of the phone belonged to a faculty member. When told about the incident years later, John loved it! Characterizing his friend as “brilliant, insightful, compelling, warm, and caring,” Nick cites among his many important professional accomplishments his “advocacy of education for democracy as central to our work.” Nick further explains that John “urged them to include colleagues in the arts and science and K-12 schools as partners in preparing teachers and renewing schools,” noting that these “parts belong together and have become the moral grounding for [him] and many other colleagues.”

Dr. Jianping Shen

As his doctoral advisor at the University of Washington, Dr. John Goodlad served as “a fatherly figure” to Dr. Jianping Shen and continues to provide mentoring and guidance. Recalling an invitation from John and his wife to spend spring break at their vacation home, Jianping describes his first fishing experience in the Pacific Ocean. After fishing for the entire afternoon at various locations, the two fishermen had come up empty. Just before returning to land, Jianping caught his first salmon and proudly held up his “precious prize.” Jianping remembers John’s gentle response: “Jianping, we have to let it go. It’s not big enough to keep….” Needless to say, Jianping enjoyed their trip even though they returned home empty handed. Jianping explains that, having set an example for educational researchers “in terms of connecting research with practice,” John is “a great scholar who inquires into and reflects upon the conduct of education [while] always having renewal projects on the ground.” Jianping adds that he is “one of the most prolific writers in the field.” Citing a book edited by Ken Sirotnik and Roger Soder, entitled The Beat of a Different Drummer: Essays on Educational Renewal in Honor of John I. Goodlad (1999), as having captured the essence and nature of his mentor, Jianping explains that the “combination of systematic empirical work and thoughtful philosophical stance makes [John] the different drummer” to many friends and colleagues.

Roger Soder

Roger Soder vividly recalls his first meeting with Dr. John Goodlad while having lunch with more than a dozen others working on a new project at the University of Washington. While many discussed various aspects of the project, John spoke above the “usual hum of voices,” specifically citing the few factors that demanded attention. Describing John’s “strong voice [as having] clear command authority,” Roger explains that “not only his astute analysis and synthesis” but also “the manner in which he talked” left an impression. This initial first impression of “John’s leadership style, voice, command authority, ability to listen to others, and strength of analysis” would prove to be “the pattern of behavior repeated many hundreds of times” over the next three decades. Invited to assist John in forming a new organization, the Center for Educational Renewal, Roger developed with John “a relationship both professional and personal, one that quickly became very close, and has remained close over the past twenty-seven years.” Roger compares his friend and colleague to Clemenceau as described by John Maynard Keynes in The Economic Consequences of the Peace (1919), who wrote that Clemenceau “alone both had an idea and had considered it in all its consequences.” To illustrate this point, Roger describes the Study of Schooling conducted by John and his colleagues that resulted in many publications, namely A Place Called School (1984). While “the ink was barely dry on thousands of copies” of the groundbreaking book, John had already conceptualized “a national study of teacher education followed by the creation of an action network of school-university partnerships that would embrace the fundamental principles of simultaneous renewal.” In retrospect, Roger explains the importance of this accomplishment: John had “led a huge national study of K-12 schooling, paused for a moment, and then set into motion (with funding) a huge national study of teacher preparation.” By “joining the two together, [both] research and practice, with the National Network for Educational Renewal,” John demonstrated “how to have long-term time perspective…[and] how to operate in both the conceptual and the practical and prudent world.” Likening John to George Marshall for his willingness “to seek information and advice from many perspectives and to weigh what was told to him,” Roger also appreciates his friend and mentor for his strong character. Remembering their many flights to schools around the United States, Roger notes that John had “accumulated untold millions of miles on most major airlines, so he could have with ease gotten first-class seats.” Despite the urging of Roger and his colleague Ken Sirotnik to book himself a first-class seat, however, John insisted on traveling in coach with them. While Roger doesn’t know “what that might mean to others,” he knows what it means to him. Learn more about John Goodlad from his friend Roger Soder.

Jane Toso

Growing up in Vancouver, British Columbia, Jane Toso remembers her uncle Dr. John Goodlad as “a mythical figure, the uncle who received many honors, travelled to exotic places, wrote books and was obviously very important in the world of education.” Admittedly more interested in spending time at family functions with her cousins who were close to her age, Jane explains that “she never spent a lot of time” with her uncle until fairly recently. As her own five children went through school, Jane often “heard his name at an educational workshop or heard him referenced in conversations about how to improve our schools.” Jane recalls the “funny reactions she got when she occasionally mentioned their family connection.” It was like being “related to a rock star!” Adding “that is what he is in educational circles,” Jane has also cherished the opportunity to spend time with John in recent years. She has also noticed that “he has a very familiar family trait-he’s a great story teller.” Additionally, Jane notes his phenomenal memory and ability to “make difficult concepts easy to understand.” Appreciating his humor and laughter, Jane adds that John has “filled in many blanks in [her] family history” through his stories. She explains that “he’s never forgotten his humble beginning and brings what he learned then into his present teachings.” “Those lessons he learned then are still relevant seventy years later” to Jane and many others-she is “proud to call him Uncle.”

Dr. Dick Williams

Praising his long-time friend and colleague, Dr. John Goodlad, for his distinguished contributions to educational scholarship, research, and practice, Dr. Dick Williams is most grateful for John’s profound influence on his career and life. Having worked with him for more than 45 years, Dick recalls the unexpected invitation from John, the newly appointed dean of the Graduate School of Education at the University of California at Los Angeles, to join his administration as an assistant dean for student affairs. Describing subsequent career opportunities as due in part to his collaboration with John on projects including the Study of Schooling, Dick emphasizes “John’s leadership skills and the significant role he played in developing the Graduate School of Education.” Explaining that the “Graduate School was quite invisible [when John] took over as dean,” Dick describes the transformation of the school into “a center for research, policy studies, and practice.” Although there had been some well-known and accomplished faculty members previously, John “successfully attracted numerous young scholars and highly accomplished senior scholars…[and] supported colleagues in developing various research and policy centers.” John “challenged the faculty and other administrators to make the Graduate School one of the top schools in the country.” Dick highlights John’s success, noting that with the help of many others, “the school had indeed emerged as a top-ranked school.” Dick explains that “John’s vision and tireless efforts played a significant part in the school’s transformation.” Also “impressed with his ability to simultaneously engage in many different endeavors,” Dick adds that John taught seminars, directed numerous doctoral dissertations, and worked as an active scholar, developing and directing several research projects. Illustrating this point, Dick notes that John also received numerous honorary degrees, continued extensive correspondence with scholars from other institutions around the world, and even worked alongside Hollywood filmmakers to prepare a presentation for the White House. Crediting John’s secretary with managing his rigorous schedule, Dick always found him to be not only “accessible, warm, and personal” but also “generous in sharing insights from his own career and in listening to and responding to questions and ideas.” Dick considers himself “fortunate to be able to visit John often and continue [their life-long] friendship.”

Dr. Carol Wilson

The opportunity to work with Dr. John Goodlad and others in the embryonic National Network for Educational Renewal profoundly changed Dr. Carol Wilson’s professional life. Describing John as a “mentor, colleague, and dear friend,” Carol and her life partner David continue to enjoy “spend[ing] some relaxing summer days with John on his beloved Lopez Island.” Recalling her amusement at the hesitancy of some school districts and universities to “work together for their mutual benefit, for their simultaneous renewal” and suggesting in retrospect that the notion of “equal partnerships struck a nerve with one or two folks not quite comfortable with the idea,” Carol recounts John’s response to a question “about what he was really after, about what he wasn’t telling the group [of education deans]. “Repeatedly rejecting the notion of a hidden agenda,” John finally “rolled up a shirtsleeve, pulled out a piece of paper, held it up, and declared, ‘Okay, you’re on to me. Here’s my hidden agenda.’ The paper was blank.” Also a member of “a zany group of Denver-area educators” known as the Last Laugh Foundation, John attended irregular meetings at various locations around town. At one such meeting, John wrote a particularly humorous proposal for funding from the LLF. Although “inclusive, thorough, and creative,” his proposal for an “inquiry into last laughs” was questioned, particularly the budget, and the project was never funded! Praising John further, Carol references Mary Oliver’s poem “Spring,” noting that his “sense of humanity, deep commitment to contributing to the renewal of our society and world, his tenacity and ability to move forward in the face of huge challenges show us what it means to love the world.” In appreciation of his “brilliant mind…and profound caring for the human condition,” Carol captures John’s essence, quoting a few verses written by Marge Piercy:

The people I love best

Jump into work head first

Without dallying in the shadows

And swim off with sure strokes almost out of sight.

Learn more about John Goodlad from his friend Carol Wilson.