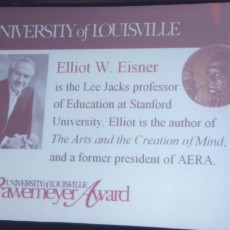

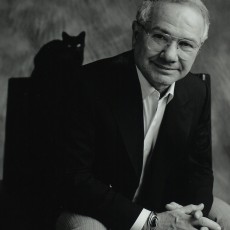

Elliot Eisner

Elliot W. Eisner is Lee Jacks Professor of Education and Professor of Art at Stanford University. Widely known for his contributions to art education, curriculum studies, and qualitative research methods, Eisner first studied painting at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago while still in elementary school. He later taught high school art classes while earning two graduate degrees in design and art education at the Institute of Design at the Illinois Institute of Technology, before earning his doctoral degree from the University of Chicago. He served as president of National Art Education Association and the International Society for Education through Art. Also a past president of the American Educational Research Association and the John Dewey Society, Eisner has dedicated his career to advancing the role of the arts in American education and in using the arts as models for improving educational practice in other fields. He has lectured on education throughout the world and received five honorary degrees and numerous awards for his distinguished educational research and scholarship including the Palmer O. Johnson Memorial Award, Harold McGraw Jr. Prize in Education, the Jose Vasconcelos Award from the World Cultural Council, the Brock International Prize in Education, and most recently the prestigious Grawemeyer Award for his book The Arts and the Creation of the Mind (2002). Also a fellow of the Royal Society of Arts in the United Kingdom and the Royal Norwegian Society of Science and Letters, Eisner has authored or edited sixteen books and numerous articles in scholarly publications, among them Educating Artistic Vision (1972), The Educational Imagination (1979), Cognition and Curriculum (1982), The Enlightened Eye(1991), The Kind of Schools We Need (1998), and Arts Based Research (2011 with Tom Barone).

To learn more about Elliot Eisner from his family and friends, visit his Reflections. To view photographs from Elliot Eisner’s personal collection, visit his Photo Gallery.

Curriculum Vitae Suggested readingsVisit the video below to watch a short overview of the interview with Elliot Eisner. Otherwise, see all four of the full interviews with Elliot Eisner below.

Video Interviews with Elliot Eisner:

Raised with his brother in a modest neighborhood in Chicago, Illinois, Dr. Elliot Eisner recalls a happy childhood in a loving, albeit lively home. Admittedly a poor student throughout his elementary and high school years, Eisner’s parents enrolled him in painting classes at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago at the recommendation of his 3rd grade teacher. Fascinated by its rare collection of paintings, Eisner explains that “[his] friends were hanging on the wall” of the Art Institute. In retrospect, Eisner credits his parents for their willingness to openly debate ideas at home and encourage his passion for art as having influenced his decision to pursue graduate degrees in design and art education. Watch this clip to learn more from Dr. Eisner about the relationship between his transformative experiences as a shoe salesman and his own development as an artist and scholar.

As part of his doctoral studies at the University of Chicago, Dr. Elliot Eisner challenged many of the leading scholars in art education by developing a typology of creativity in the visual arts. Arguing that creativity was content and form specific rather than a common generic function across fields and processes, Eisner earned the recognition of the American Education Research Association for his outstanding dissertation. He even received his first job offer at Ohio State University following his open criticism of a prominent educational researcher in front of an audience of nearly 2,000 conference attendees. In this clip, hear more from Dr. Eisner about his request for a promotion and The New York Times article that nearly changed the course of his career.

Once told that he would be unable “to wear two hats,” Dr. Elliot Eisner has cultivated his passion for both art and education. Describing education as “the invention of yourself,” Eisner has devoted much of his career to developing the concepts of connoisseurship and critique. Eisner explains that there are “two wings to looking at the world,” describing connoisseurship as one’s ability to “see what there is to see” through an appreciation of both the subtleties and complexities in art, and critique as “the transformation [of art] into a form that enables others to see what [one has] seen.” Applying these concepts to education, Eisner suggests that educators can develop the technical skills necessary to “locate the possibilities for art to function” and provide students with opportunities to make art through stories, music, and painting. Watch this clip to learn more from Dr. Eisner about the similarities between checkerboards, cooking, and art.

Praised by his colleagues for his steadfast commitment to his students, Dr. Elliot Eisner cites his role as a mentor among his most significant professional achievements. Eisner also shares his advice for graduate students and early researchers, encouraging them to “think outside the box” by looking at classrooms with new eyes. Explaining that one must watch a baseball game with a keen eye in order to understand how it is played, he adds that descriptions of the actions are insufficient. Eisner also has a way with words—many of his friends claim that his vocabulary rivals that of the Oxford English Dictionary! Watch this clip to hear more about Dr. Eisner’s latest research and his critique of “material that has no spirit.”

Amrein-Beardsley, A. (2012, April 22). Inside the Academy video interviews with Dr. Elliot Eisner [Video files]. Retrieved from /elliot-eisner

Dr. Tom Barone

Characterizing their early relationship as that of student and mentor, Dr. Tom Barone describes his deep friendship with Dr. Elliot Eisner. Explaining that from Elliot and his wife “there came never ending kindness, [and] for [his] part, there was enormous gratitude.” Tom praises his long-time friend and colleague as an educational leader whose focus on “the capacity of imagination and judgment in the educational process [has dominated his] pedagogical efforts throughout his life and career.” Describing “a mischievous and playful side of Elliot that [he] hadn’t known existed,” Tom recalls a trip with his wife Margaret to Utrecht in the Netherlands to continue collaborating with his friend on a research project. Graciously serving as hosts and tour guides, the Eisners escorted their guests to a number of interesting sites and venues in Utrecht and the surrounding area. During each excursion, Elliot “kept teasing [them] with promises of one final tourist destination, one of the most amazing of all that he had seen in Holland.” Tom describes the last evening of their stay during which they accompanied the Eisners on a car ride along a nearby canal. Tom recalls his surprise at seeing a row of houseboats along the bank of the canal each with a large picture window in front-they had just passed through the red-light district! In addition to his lighthearted sense of humor, Tom notes his friend’s prodigious professional accomplishments, citing his Presidential Speech at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association “as powerfully composed, masterfully delivered, [and] employing artistic visions to emphasize many of his main ideas.” Describing this event as “a sure sign that the foremost champion of a realm of human endeavor severely marginalized [within the association], the arts, had taken the spotlight,” Tom recalls that “it gave [him] goosebumps.” Having “led [students and sometimes reluctant colleagues] to understand the need to subjugate the technical elements…of educational program design, teaching, research, and evaluation, to the larger dimensions of artistry and criticism,” Elliot’s courage remains “a hallmark of [his] intellectual leadership.” Rather than “advance the cause of art-based educational research” at the expense of other scholarship, Tom adds that Elliot “merely insist[ed] upon space for additional settings at the research table.” Capturing the essence of his long-time friend, Tom explains that “so many members [of the field of education] are more fully alive” in large part “thanks to the pedagogy of Elliot Eisner.”

Dr. Larry Cuban

Dr. Larry Cuban describes his long-time friendship with Dr. Elliot Eisner, explaining that their offices were located close to one another in the same hallway at Stanford University’s School of Education. Having gotten “together weekly for coffee [for many years now] to discuss educational issues,” Larry and Elliot often “reminisce about how [they] grew up in different cities but shared many similar experiences, discuss what’s been happening with [their] families, and tell stories to one another.” Noting that many stories have been repeated numerous times, Larry adds that “on many occasions, after one of [them] had begun to tell a story or joke, the other would recognize [it] and [they] would complete it in unison!” Indicative of their friendship over the past 20 years, Larry and Elliot continue to laugh about “friends, memories, and the importance of humor.” Praising Elliot for his distinguished contributions to academia, Larry recalls a particularly memorable faculty meeting at Stanford during which colleagues received recognition for their professional accomplishments. Having been awarded three honorary degrees already that year, Elliot was not recognized at that final meeting of the academic year. Teased by a colleague that he was “slowing down,” Larry describes the subsequent round of applause for Elliot “in recognition of his stature in the field” adding that “of course, he went on to collect more honorary degrees as the years passed.” Larry cites Elliot’s “fresh and contemporary Deweyian rationale for education and the arts at a time when schooling has become a packaged commodity, a product delivered by technocrats who measure and weigh learning” as his most significant contribution to the field. Also describing his friend’s “fluency in communicating ideas and emotions…about things that mattered in education and life,” Larry notes that he cannot count the number of standing ovations given to Elliot by large audiences including students and educators. Widely respected for his ability “to convert his passion for ideas about the arts, goals of education, and engaged criticism into words and feelings that grip listeners,” Larry commends his friend for moving educators “to be better in teaching children, supervising teachers, administering schools, and researching educational issues.”

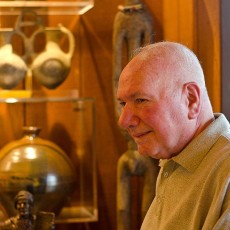

Dr. Stephen Dobbs

Characterizing Dr. Elliot Eisner as his “advisor, teacher, coach, mentor, confidant, guide and inspiration,” Dr. Stephen Dobbs explains that they “became both professional colleagues as well as personal friends” over the past four decades. Impressed by his ability to “toss off [words like] ‘isomorphic,’ ‘noetic,’ and ‘pulchritude,” Stephen notes that Elliot “loves language, and language loves Elliot.” Adding that “he has a vocabulary that rivals the Oxford English Dictionary,” Stephen explains that his friend “doesn’t just use words, he feels them, he tastes and savors their qualities as they roll off his pen or his tongue.” Insisting that to cite a single personal or professional achievement would be inadequate, Stephen praises his friend as “a thinker [who] has contributed more than his share of ideas in philosophy of education, arts and aesthetic education, curriculum, and evaluation,” noting that Elliot also “raised a family, gave 24/7 access to his students, and developed sturdy friendships.” He further characterizes Elliot as “always ready to share perceptions and to pursue the teachable moment,” adding that his friend has a marvelous collection of stimulating, beautiful pieces of African Art. Explaining that Elliot is self-taught in this area and understandably proud of his collection, Stephen captures the nature and essence of his friend, observing that his “imagination, connoisseurship, and excellence [are] reflected in his love affair with art.”

Linda Eislund

Explaining that she and her father Dr. Elliot Eisner “have a very close relationship,” Linda Eislund and he “discuss everything that happens in [their] lives, from the mundane details of daily life to [their] deepest concerns.” Describing “many of the lessons that her dad taught her [as having] taken place in some of the most wonderful classrooms,” Linda shares her memories from her childhood. Her father quizzed her on the meaning of proverbs around the dinner table, taught her “to appreciate art, color, design, and composition” at the museum, demonstrated how to haggle at the flea market, and always encouraged her to judge the quality of a garment by “turning over the lapel to see if it’s hand stitched.” Fondly recalling these experiences, Linda explains that she “was the lucky recipient of the teachings of a man who found great joy in sharing what he’d discovered about the world,” adding that she couldn’t think of “a better way to learn.” Often invited to join her father on a ride to the local A&W to enjoy Papa and Baby burgers with Edy’s ice cream, Linda relished those trips “in his red convertible, with the top down, driving up to Skyline Boulevard, and then back down the mountain.” Adding that “his humor, laughter, and general love of life were contagious,” Linda describes the frequent dinner parties at which “her mom cooked beautiful meals for everyone and her dad held court, leading interesting discussions about political and world events, education, and friend’s lives.” Elliot “was known for cracking jokes that he thought were hysterical, but that weren’t always that funny”-he was often “his own best audience and would end up laughing at his own jokes unable to stop!” Also praised by his daughter as “a thinker, who loves exploring how ideas that seem simple are really complex or how issues that seem black and white, are actually grey,” Elliot has “challenged his students to think deeply about education.” Linda shares her sentiment and that of many others, adding that her dad has “conveyed his ideas with clarity and enthusiasm, both in writing and in the classroom, and because his students have been influenced by those ideas, he has created an important legacy in the field of education.”

Ellie Eisner

Having shared 55 years of married life with Dr. Elliot Eisner, his wife Ellie describes their relationship as “one of a loving partner, supporter, [and] assistant,” adding that “Elliot has been a wonderful husband, father, and grandfather [throughout] those years.” Also proud of her husband for his profound contribution to academia as an educational researcher and scholar, Ellie explains that a member of Elliot’s doctoral committee once told him that “he would never be able to wear two hats-one in education, one in art education-[and] that he would have to make a choice.” She notes that “the academic community now knows just how successfully he proved that notion wrong…he is not only able to wear two hats, but he has also used both to inform [the other] so keenly.” In addition, “he helps people open their minds, eyes, and hearts to the world around them…he has been courageous, a maverick, [and] brilliant.” Fittingly characterized by his wife as a mentsch, a Yiddish word referring to a nice and decent person, Elliot “highly values his relationships with people…[feeling] a sense of pride and joy in [others’] accomplishments.” Ellie characterizes her husband as the “educator/enlightener,” explaining that he is “intellectually stimulating [and] ready to engage with humor and affection” those around him. She also adds that he has never been preoccupied with looking in the rear view mirror. According to his wife, Elliot is “always looking ahead…to see and create the wind that could blow for students, teachers and the field of education.”

Steve Eisner

Dr. Elliot Eisner and his son Steve share a “very close relationship filled with warmth, playfulness, humor, honesty, and intellectual engagement.” Explaining that his father has “always been there for [him] in difficult times, with sage words of advice and support,” Steve jokingly adds that “of course, in true Elliot Eisner style, he will offer his opinion even when unsolicited! But just as inevitable, his judgment consistently turns out to be spot on.” Recalling memorable childhood experiences with his father, Steve describes Elliot’s fondness for pickled herring. Having bought the herrings out of wooden pickle barrels in Chicago as a young boy, Elliot searched for a jar of the small fish while on sabbatical in Europe. Entrusted with carrying the much-anticipated treat, Steve remembers his father’s expression when the jar slipped through the bottom of the wet bag. “Forlorn and distraught at the notion that his pickled herring…would go to waste without his being able to savor the experience,” his father stooped down on his knees to wade through shards of glass with his fingers to find the edible herring slices!” Also noting Elliot’s excitement at finding a great bargain, Steve remembers monthly visits to the flea market with his father and sister. On one such occasion, Steven vividly describes their “hot” bargain for the day-a “Polo pin striped three piece suit” in just his size! Also immensely proud of his father for his personal and professional accomplishments, Steve explains that “he continues to cope with the challenges of Parkinson’s disease…continuing to meet each day with strength, perseverance, and determination” while displaying “at his core an incredibly strong work ethic, driven by an indefatigable desire to advance the visibility and importance of the field of art education.”

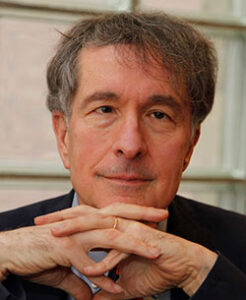

Dr. Howard Gardner and Dr. Ellen Winner

Dr. Howard Gardner and his wife Dr. Ellen Winner have enjoyed their friendship with Dr. Elliot Eisner for more than 40 years. Howard recalls his early collaboration with Elliot when both were consultants to “a promising but ill-fated arts television show for children” as the beginning of their long-time friendship. Admonished by Elliot for his failure to have joined the American Educational Research Association, Howard adds that he promptly became a member and describes his engagement in rousing debates with Elliot at several of the annual meetings. After these well-attended debates, Howard “used to joke that out of an audience of 1,500 attendees, 1,498 supported Elliot!” Howard cites these debates as evidence that “colleagues and friends can talk about a serious issue seriously and remain good friends”-something rarely seen today in politics and even less frequently in the academy. According to Howard, Elliot “reminds us of what education can be like, if we consider the whole range of knowledge…human beings, and human nature,” adding that his friend “does not succumb to the trendy, [and even] actively critiques it.” Illustrating “the importance of the arts, experience, connoisseurship, and values,” Howard explains that “our whole understanding of educational philosophy and educational practice would be diminished without the wit and wisdom of Elliot Eisner.” Even though Elliot has received “every conceivable honor that can be bestowed, from academies and institutions all over the world,” his greatest achievement “has been the many colleagues and friends that he has influenced-either directly, through mentoring, or arguing (!), or indirectly through his writing and public addresses.” Ellen echoes this sentiment, noting that “Elliot has wonderful insights…[and that] he is an inspiration to all of us who value the arts, who value education, and who value the arts in education.”

Dr. Howard Gardner and his wife Dr. Ellen Winner have enjoyed their friendship with Dr. Elliot Eisner for more than 40 years. Howard recalls his early collaboration with Elliot when both were consultants to “a promising but ill-fated arts television show for children” as the beginning of their long-time friendship. Admonished by Elliot for his failure to have joined the American Educational Research Association, Howard adds that he promptly became a member and describes his engagement in rousing debates with Elliot at several of the annual meetings. After these well-attended debates, Howard “used to joke that out of an audience of 1,500 attendees, 1,498 supported Elliot!” Howard cites these debates as evidence that “colleagues and friends can talk about a serious issue seriously and remain good friends”-something rarely seen today in politics and even less frequently in the academy. According to Howard, Elliot “reminds us of what education can be like, if we consider the whole range of knowledge…human beings, and human nature,” adding that his friend “does not succumb to the trendy, [and even] actively critiques it.” Illustrating “the importance of the arts, experience, connoisseurship, and values,” Howard explains that “our whole understanding of educational philosophy and educational practice would be diminished without the wit and wisdom of Elliot Eisner.” Even though Elliot has received “every conceivable honor that can be bestowed, from academies and institutions all over the world,” his greatest achievement “has been the many colleagues and friends that he has influenced-either directly, through mentoring, or arguing (!), or indirectly through his writing and public addresses.” Ellen echoes this sentiment, noting that “Elliot has wonderful insights…[and that] he is an inspiration to all of us who value the arts, who value education, and who value the arts in education.”

Dr. Bennett Reimer

Having known each other professionally for several decades, Dr. Bennett Reimer and Dr. Elliot Eisner have collaborated on various projects together and shared many phone calls about the state of their respective fields, specifically music and art education. Adding that their “friendship has grown and deepened remarkably” over the past few years, Bennett notes that he is three months older and relishes an opportunity to remind Elliot “to have some respect for his elders.” In spite of their good-natured jests, Bennett explains that “few friends in either of [their] lives have been able to share experiences and reflections as openly and deeply as [they] have become able to do.” According to his friend, Elliot is “naturally humorous when not in the limelight [and when] given a relaxed and comfortable setting, he enjoys the thrust and parry of joking repartee,” adding that “his wit is quick and clever, especially given his mastery of language.” Both “especially enjoy kidding about each others’ accomplishments, in both chiding yet respectful ways,” explains Bennett who insists that “no airs [are] tolerated in these interplays, [and] any hints of egotism [are] quickly and hilariously shot down by the other.” Although both enjoy these witty exchanges, Bennett also praises his long-time friend for “the enormous breadth of his intellect combined with his penetrating depth of insights into each of the diverse fields with which he has dealt…[he has] truly impressive wisdom, not limited to one particular area of expertise.” Bennett captures the essence and nature of Elliot, describing him as a “model professional [with] admirable humaneness [and a] indefatigable contributor to our shared intellectual heritage.”

Dr. Matthew Thibeault

Dr. Matthew Thibeault considers his former doctoral advisor at Stanford University, Dr. Elliot Eisner, to be both a mentor and friend, explaining that while teaching public school near the campus, he remained in constant contact with Elliot throughout the experience. Explaining that “Elliot has so many fantastic examples from multiple domains, relating the arts to physics or mathematics or the work of a chef, that many people feel his knowledge knows no boundaries,” Matthew shares a memorable story. While observing a geometry class from the back of the room, both were listening to the lecture and discussion on the Pythagorean theorem, when Elliot leaned over to whisper in Matthew’s ear, “I have no idea what they are talking about!” Also recalling his attendance at a presentation given by Elliot to a group of superintendents, Matthew describes Elliot’s masterful ability to “get them all talking about the importance of the arts and aesthetic experiences as if they were art teachers themselves.” Having mentioned his amazement to Elliot a few weeks later, Matthew recalls his friend’s reply: “These superintendents have many duties and responsibilities, but in their heart of hearts they got into the field of education for other reasons.” Matthew cites this story as capturing what he believes “to be something essential about Elliot’s contribution to the field, namely, his ability to reconnect those engaged with education with their heart of hearts, why they became educators in the first place.”

Dr. Bruce Uhrmacher

Dr. Bruce Uhrmacher describes his experiences as a former student of Dr. Elliot Eisner, explaining that Eliot “will always be a mentor to [him] through his works, words and deeds.” When co-editing Intricate Palette: Working the Ideas of Elliot Eisner (2004) with Jonathan Matthews, Bruce describes Elliot as “most supportive and incredibly helpful throughout the writing and publishing process,” laughing at the role reversal when Elliot looked up the citations. Despite Elliot’s well-known sense of humor and the warmth of their times together, Bruce notes that his mentor “relates to many of his students and colleagues with a sense of urgency; that together [they] are working on important educational matters and time is of the essence.” Illustrating this point, Elliot once delivered a dinner speech, insisting that he had “no intention of conforming to such expectations” as lightheartedness, humor, charm, or nostalgia, adding that he “care[d] too much about the issues, [got] too much pleasure dealing with ideas, and for the life of [him], [could not] forgo the opportunity that this podium, on this occasion, with this audience, ma[de] possible.” As a world-renowned educational researcher and scholar, Elliot “has affected and changed the educational landscape” in many ways by “redefining what is important in art education,” making room for “artistic endeavors to count as important scholarly inquiries,” “providing the arguments for employing [other] forms of representation…[to] allow students to come to know the world,” and helping others “question the purpose and form of schooling [by] pushing [their] thinking on issues pertaining to objectives, standards, creativity, imagination, educational reform, and aesthetic literacy.” Expressing his sentiment and likely that of many other former students, Bruce describes Elliot as “a connoisseur of life’s potential, and artistic in his abilities to define, redefine, and stretch educational possibilities.”